Ecology of the Book

Presentation by Susan Hawthorne | International Alliance of Independent Publishers | Pamplona Spain | 23 November 2021

Production: organic farming and organic publishing

Farida Akhter in Bangladesh is both a farmer and a publisher and she writes of farming that “the New Agricultural Movement is not to produce more food for consumers, but to create life, diversity and Ananda [to live a happy life]” (2001). I too come from a farming background and when Renate Klein and I set up Spinifex Press in 1991, we made a conscious decision to stay small. We were not interested in growth for growth’s sake, instead what we wanted was small-scale publishing, like the organic farmer who has her best results on limited acreage. Staying small enables the farmer to produce something unique, to retain flavour that can’t be produced industrially. Industrial scale agribusiness claims that organic is only for the rich, but Farida has shown by example how people with few resources can create nutritious food grown without pesticides or the intervention of big seed companies

The world’s paper is produced industrially in plantation forests. Native forests are clear-felled and replaced by exotics. This destroys biodiversity. The bigger the publishing company the bigger the print runs. In turn, large print runs create excess stock returned by booksellers: wasted books, wasted paper, wasted trees. Returns lead to unnecessary use of oil and diesel and create high book miles. As a small independent, we have small print runs, PODs, ebooks and very low returns. We also insist that our papers are either FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) and PEFC (Programme for Endorsement for Forest Certification). The latter are mostly Australian based. We have looked into the use of inks – whether vegetal or chemical – and at this stage because soy is the basis of most vegetal inks, and because soy is a problematic industrialised crop, we have not moved towards using those inks. While we have noticed quite a few journal publishers using unlaminated stock on covers, we have not yet gone down this path, but it is something we are considering.

Other aspects of production include ebooks which we have been producing since 2006. With a few exceptions, almost our entire list is digitised and it is a standard part of our publication of a book. Co-productions – working with other independent publishers – has been a consistent part of our process since 1992. We have worked with publishers in India, South Africa, Canada, the Philippines, USA and UK.

In summary, reducing book miles, keeping print runs short, using paper grown in registered sustainable forests and staying small are at the core of keeping waste out of our production systems. I believe that organic publishing produces better books and wish that readers understood more about the ecology of publishing. A sustainable industry is one in which books have more than a three-month shelf-life. We have discovered that zoom launches can be just as successful as book tours that involve expensive air miles. Small is beautiful, and so is independent.

Interconnection between the different actors

What about content? Our books are more than products, they are the considered thoughts of authors, the work of editors, designers and typesetters, all of which affect the look and feel of a book, its readability and the way a book sits inside a culture. The ideas and the way in which a book is received are important. The selling and marketing of books is often a challenge for small and independent publishers who cannot pay to have our books noticed. In the mega publishing world publishers become booksellers; booksellers (like Amazon) become publishers; they set up different language offices where translation can happen in-house; they sponsor writers festivals that put their authors on the biggest stages. These are systems in which the power of money distorts speech into a commodity. It removes the imaginative because the books published by these systems are formulaic, genre bound and resemble a dangerous weed that has infested an ecosystem destroying biodiversity.

For bibliodiversity to be resilient we need the concept of fair speech. In 2010, Betty Mclellan in her book Unspeakable invented the term ‘fair speech’ and I picked up on it in my book Bibliodiversity. Fair speech can be compared to fair trade and free speech to free trade. Most of us are familiar with the idea of free speech, but what is rarely taken into account is the libertarian nature of free speech. Pornographers are all for free speech because it makes them billions of dollars in profits. What we get is the speech of the powerful. By contrast, fair speech takes account of context and of the power relations between the speakers. The freedom to be a bigot takes precedence over fairness in social relations.

To summarise the difference:

Free trade / free speech favours the powerful

Free trade / free speech fosters and entrenches inequality

Free trade / free speech focuses on the individual

Free trade / free speech ignores quality of life (McLellan 2010 pp. 52-58)

Fair trade / fair speech decentralises power

Fair trade / fair speech fosters justice and fair treatment

Fair trade / fair speech focuses on the common good and engagement

Fair trade / fair speech highlights the importance of life over justice

The upsurge of cancel culture purports to be an instance of fair speech because it claims to be the disempowered speaking out. But in fact, it is an appropriation of the free speech model that enables those who feel silenced to speak up whatever the cost. Cancel culture is used by those with loud voices steamrolling over their targets. An instance of this to which Spinifex has been subjected, is the cancel culture of the transgender lobby, funded by billionaires who run medical and pharmaceutical companies making huge profits from lifelong use of dangerous drugs and dangerous surgery that will affect the lives of the now mostly young women (especially lesbians) for the rest of their lives. Several of our authors have been subjected to cancel culture simply for writing on this subject.

Bibliodiversity

Just as biodiversity is an indicator of the health of an ecosystem, the health of an eco-social system can be found in its multiversity and the health of the publishing industry in its bibliodiversity. These are complex systems that are in dynamic balance. Here are six principles that are important to foster bibliodiversity.

Networks: interconnected social relationships such as that sponsored by the Alliance. It could include a poem that generates a musical composition or the ways in which traditional knowledges pollinate the culture. We are seeing a lot of this in Australia with many works by Indigenous writers, artists, film makers.

Nested systems: this is about systems within other systems. Publishing houses are nested within specific cultures, for example Spinifex is nested in the feminist culture both in Australia and internationally and we have a responsibility towards those cultures and our content reflects that.

Cycles: members of an eco-social system depend on the continual exchange of energy through ideas and storytelling.

Flows: every culture needs a continual flow of ideational energy. Publishers have a responsibility to contribute to that flow in respectful and imaginative ways.

Development: all culture changes over time whether it’s a child’s story or the shifts in technology that changes how stories are told. Consider orature (oral storytelling, myth and legend) to literature (papyrus, palm leaf, hand-copied manuscripts, printed books); and finally the shift from the printed book, to ebooks and digital devices.

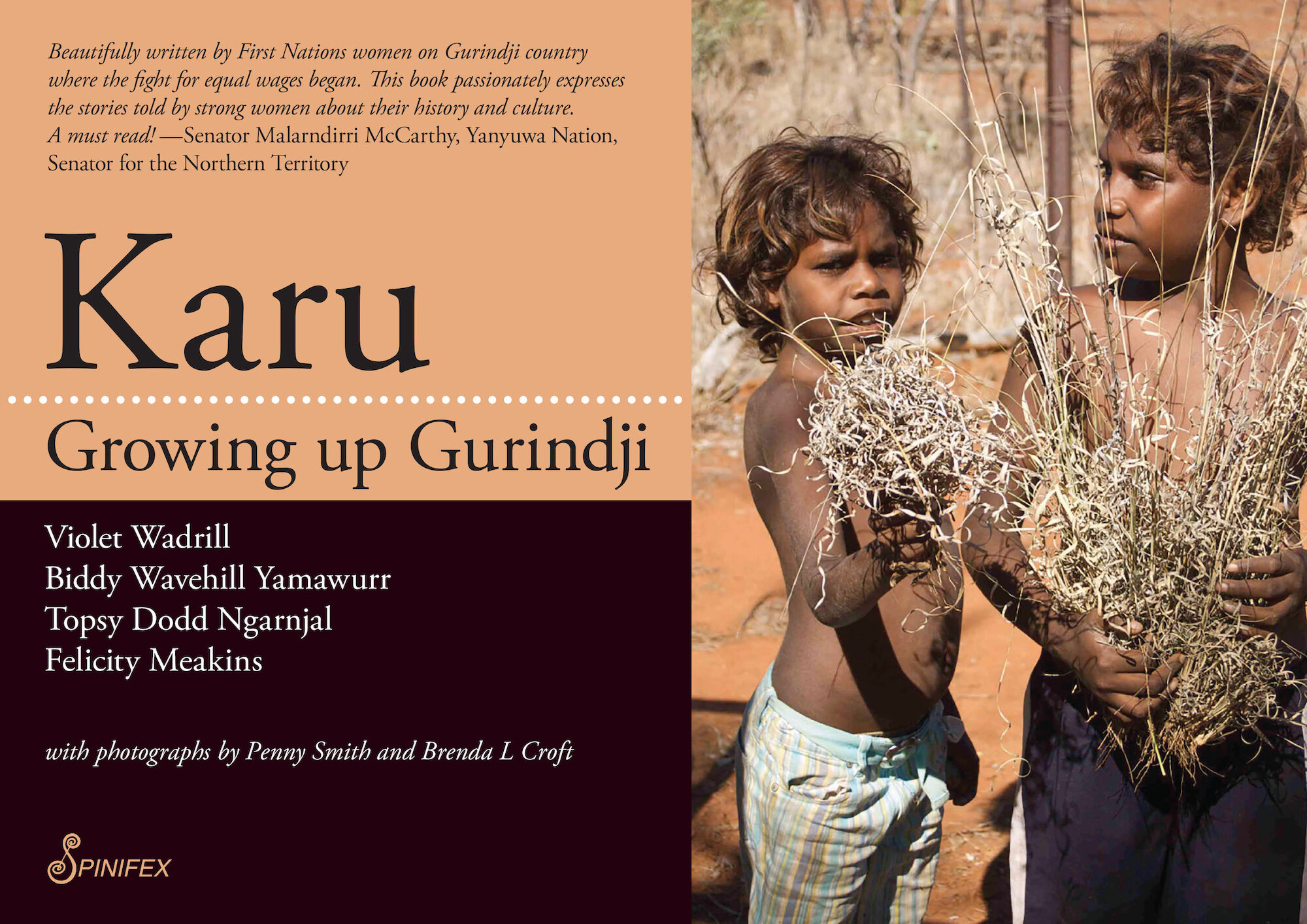

Dynamic balance: this is achieved with dynamic feedback loops so that a bibliodiverse and multiverse community maintains a reasonable steady state. It is the basis of cultural resilience. The importance of languages. For Spinifex, the publication of the book Karu: Growing Up Gurindji by three Aboriginal women elders and a translator in Gurindji and English is a political and cultural statement about Indigenous languages in Australia. QR codes in the book allow the reader to listen to the spoken language. This was a bringing together of new and old technologies.

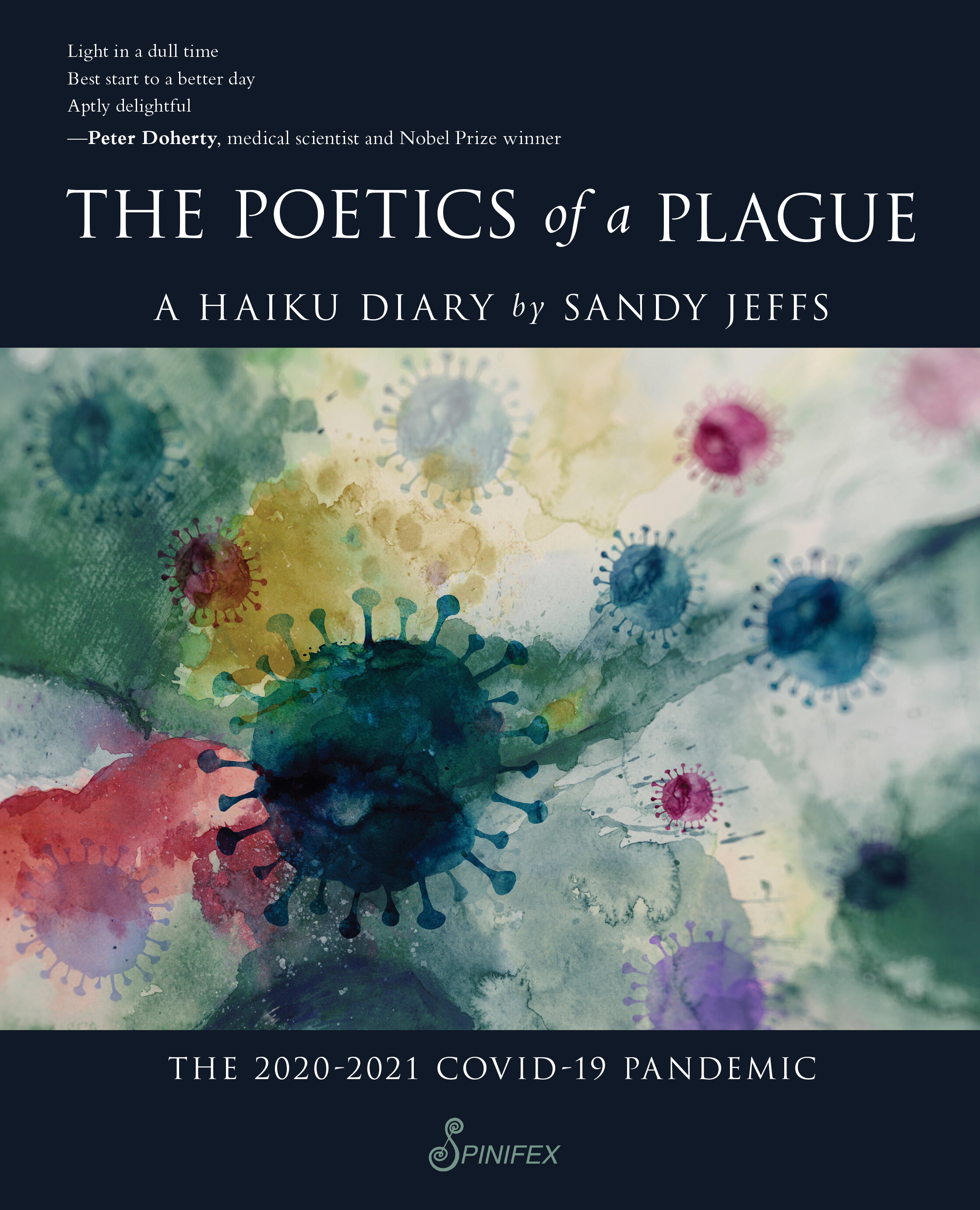

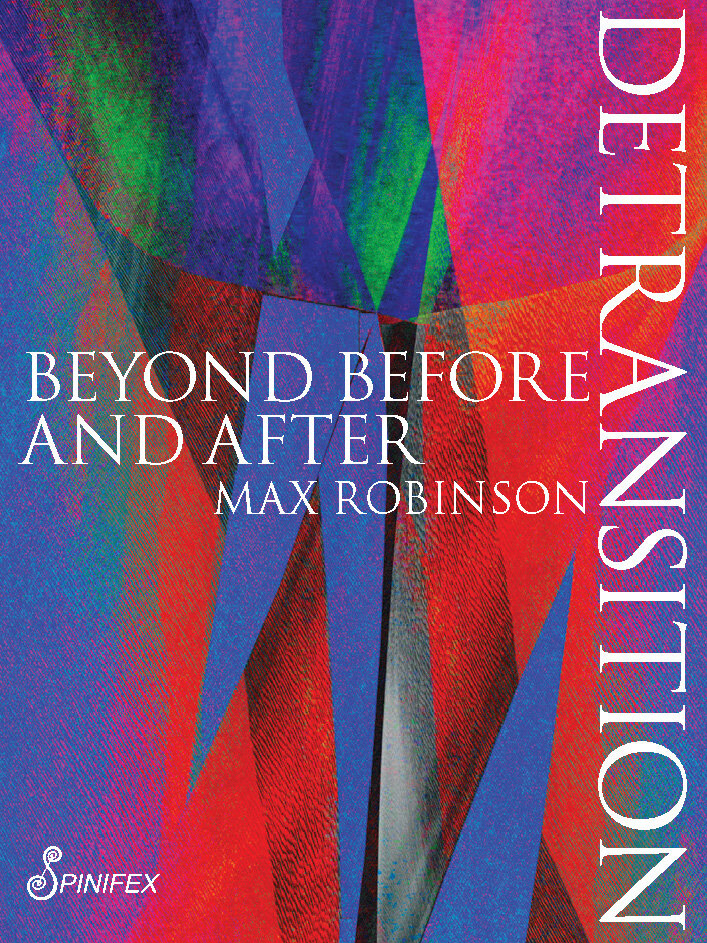

I want to give a few examples of books which contribute to bibliodiversity. With almost 300 books published these are just a few of them.

The Poetics of a Plague, A Haiku Diary by poet and disability advocate Sandy jeffs. Written in response to the world’s longest lockdown in Melbourne during 2020 and 2021. It is funny, insightful, sometimes melancholic but always full of clear and precise observation of the human condition.

Detransition: Beyond before and after by Max Robinson a young US lesbian activist who unpacks the profitable industries involved in this wholesale violation of women. She refers to the assimilation industries including liposuction, rhinoplasty (nose operation) and blepharoplasty (eye operation) – all of which are profitable surgeries to ‘normalise’ those who are different – ie fat, Jewish, Asian.

Towards the Abolition of Surrogate Motherhood, an anthology produced in collaboration with the International Coalition for the Abolition of Surrogate Motherhood based in Paris. French and Spanish editions of the book will be published in 2022. This is an area in which women living in poverty, in countries with lax or no laws about exploitation are used as ‘baby machines’.

Locust Girl by Philippine-Australian writer Merlinda Bobis, a novel about climate change, the theft of water and the consequences of war. It won the Christina Stead Award for Fiction in 2016.

All these books contribute to bibliodiversity, taking up issues of poverty, war, Indigenous languages, profiteering on women’s bodies, disability and lesbian exclusion. As the US singer songwriter Alix Dobkin said, “There are only two responses to freedom. One is trying to control everything. The other is to be creative and take risks.” We are on the side of creative risk taking.

One final statement: our abuses of nature are resulting in an over-heated planet driving headlong towards catastrophic climate change. Our abuses of culture are resulting in an increasing levels of violence reflected in books that are the cultural equivalent of climate change: promoting the violence of pornography, hatred and misogyny, monocultural and racist violence against the ‘other’, and war-mongering. Independent publishers must keep publishing risky, innovative and long-lasting books out of our passion for telling stories. Books from now for the future.