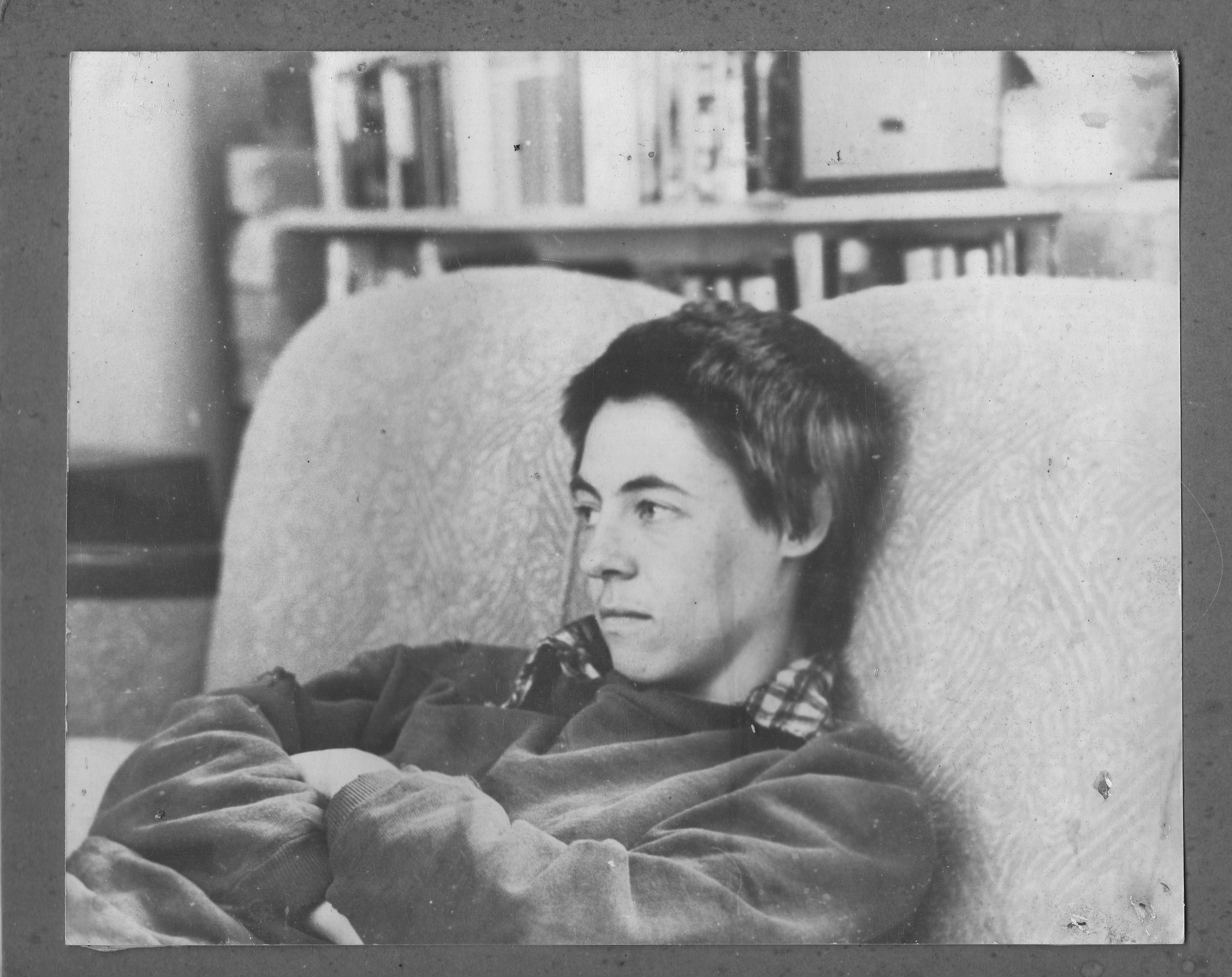

The Best Decision of My Life by Susan Hawthorne

I was four months too young to contribute a piece to Not Dead Yet. Now that I have crossed the 70-year threshold here is my contribution.

I am riding my bicycle as fast as I can, doing broadsides on the gravel with my younger brother. The second time round as I approach the overhanging cedar, I take my hands off the handlebars and grab the branch. The bike crashes.

On the first of July each year – my mother’s birthday – shearing begins and in November the summer wheat and oats harvest begins. Both these times give my brother and I lots of opportunities to hang by our knees and drop into the fleeces of wool or the wheat grains. We walk across to the woods, a large area of scrub filled with Callitris pine. From this we build cubbyhouses of increasing complexity. Sometimes, my older sister joins in and makes gardens or curtains.

At age 12, I am sent off to boarding school in Melbourne. If I were to stay on the farm, my schooling would end at 15. I did not do terribly well at boarding school, I became a middling student and managed to fail a subject every single year, including English literature. My final year results meant that I did not get into university, instead I went to Teachers College. In some ways that became a blessing because it allowed me to be pretty wild for three years, become a hippy, drop some drugs and discover my love for philosophy.

At age nine, I said out loud that I would not marry until I was 23, an ancient age to a nine-year-old. The Women’s Liberation Movement saved me from a life I was not enjoying at age 22. I joined the Women’s Liberation Group at La Trobe University in 1973, became involved in activism and in late 1974, I left my male partner and moved into my lesbian life. I have never looked back. It was the best decision of my life.

The early days were heady from the first Women’s Dance to my debut as a graffiti artist. There was a cigarette brand called Bradfield which had the jingle “from Adam’s Rib to Women’s Lib” and later the words “Not mild” suggesting it was a real man’s cigarette. What we were doing was adding ‘But sexist’ after the ‘not mild’ tagline. Driving around in the dark we went looking for the billboards. We found one to graffiti in a northern suburb of Melbourne and chased down the others we knew about. Every single one had already been sprayed. There was a great sense of satisfaction knowing that we were part of a movement and that other women were out there doing the same as us.

In 1975, I joined Melbourne’s Rape Crisis Centre, volunteering to answer the phone, accompany women to court and to inform myself about rape. In my relatively short heterosexual phase, I had experienced two attempted rapes and one rape, so I had good reason to join this collective.

With three years of wild times behind me, I was ready to really enjoy my life at university. 1973 was the same year when, after the election of Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, universities were free and there was a sudden influx of mature age women students. Over three years, I enrolled in Revolutionary History, African History and Women’s History. I also enrolled in Zoology and Philosophy. At the end of my third year in Philosophy I was offered a place in Honours. I decided that I wanted to look at the theory of separatism. It was a year I really treasure and the thesis I wrote was called In Defence of Separatism. It was finally published in 2019.

As most Australian do, I then travelled overseas for three months, living in a squat in Lambeth followed by travel through Europe mixing hitchhiking and overnight train travel. Crete was a huge eye-opener to me, and I relished the archaeological riches, the mythic history, and the language. After a few weeks I could decipher the Greek alphabet and when I returned to Australia, I studied first Modern Greek and then Ancient Greek. I’ve incorporated these mythic elements into my novels and poetry, with more recent studies in Sanskrit and Latin filling out the mythic substratum further.

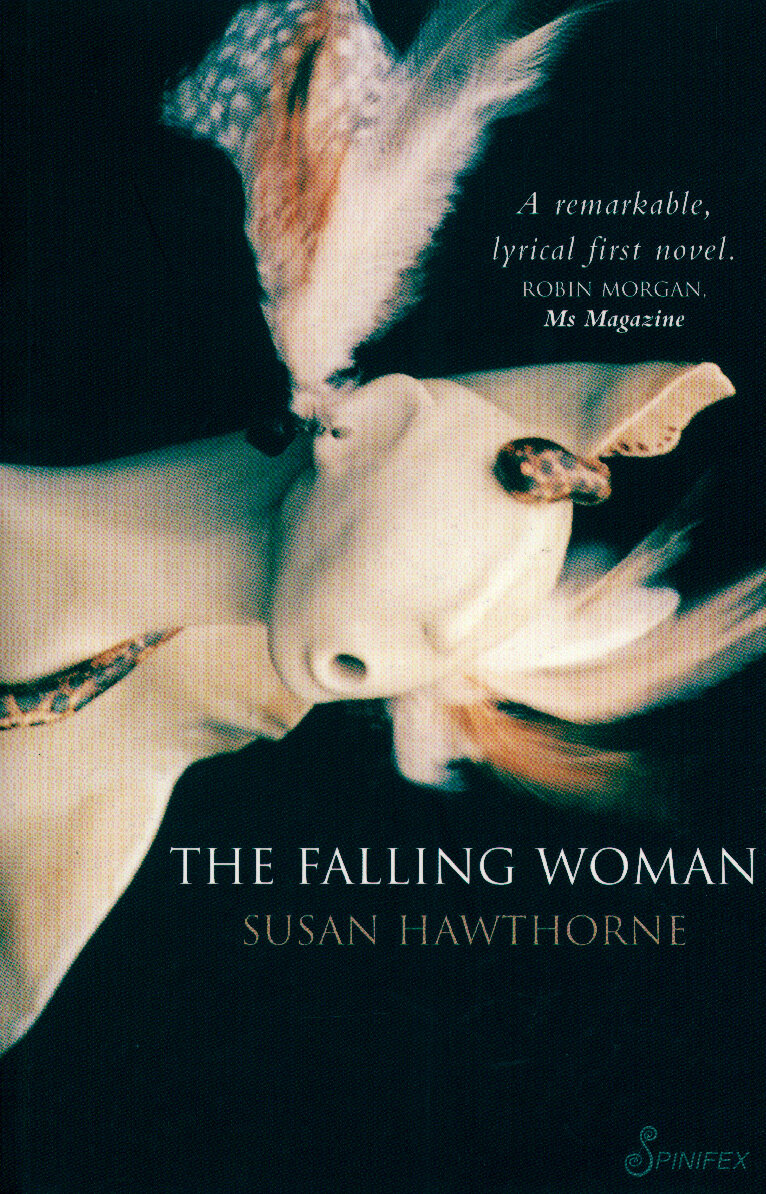

The following years were a mix of part-time jobs, casual jobs and long stretches of unemployment. I was living on the smell of an oily rag. This was when I began writing seriously: stories, book reviews, the odd poem and in the early 1980s I began to write The Falling Woman, a novel which explores the interlocking experiences of epilepsy and lesbian existence. It was a double coming out.

My long period of unemployment kick started me into publishing though that was still some years away. As part of a government-funded programme I became the Writing, Music and Theatre Co-ordinator of the Women 150 New Moods Festival. I decided to challenge the celebration aspect of 150 years of colonisation by highlighting writing by Aboriginal women as well as by migrant, working-class women and lesbians. The festival ran for nine days, and keynote speakers were Audre Lorde and Keri Hulme. In my theatre role, Eva Johnson’s play Tjindarella, an anti-fairy tale about invasion and colonisation toured to Melbourne. With my music hat, I organised the first all women composers programme conducted by a woman at the Melbourne Town Hall.

I took off for Greece again after the festival finished where I spent more time, and by now, as I had been studying Ancient Greek for some years, I could have minimal conversations in Greek.

My entry to publishing came in 1987 with a job as an editor at Penguin Books Australia. The opening occurred because they were looking for an editor with knowledge of women’s writing. Dale Spender had proposed a series of books on Australian women’s writing, some reprints of out-of-print books, others new critical books that covered this area. This became the Penguin Australian Women’s Library. During my four years as an editor at Penguin I worked with many novelists and poets and was responsible for bringing in books by Indigenous writers, as well as writers from migrant backgrounds and lesbian writers.

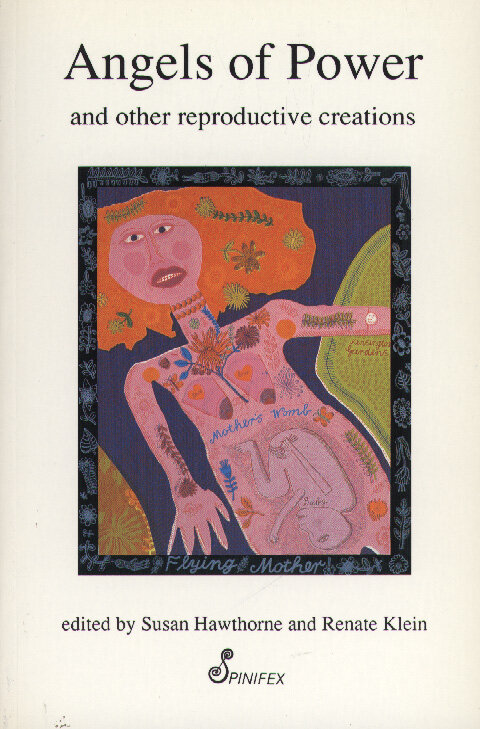

In 1991, Renate Klein and I founded Spinifex Press. We discussed the idea while on holiday at Kakadu National Park because we were both frustrated by the difficulty of getting good radical feminist books published. Postmodernism had taken over the shelves and Gender Studies was in the process of erasing Women’s Studies. In 1992, we made a bid for the International Feminist Book Fair to come to Australia in 1994. We won the bid and so began another two years of frantic organising. Our theme was Indigenous, Asian and Pacific Writing and Publishing. Thousands of audience members attended with at least 350 writers on the programme.

Renate and I travelled to Bangladesh in 1993 for a conference organised by Farida Akhter: ‘Peoples Perspectives on Population’. For around five days, 64 women discussed the current state of the world, globalisation, Structural Adjustment and a host of other subjects. Maria Mies was the facilitator in the group I was in and after several days I sat down and wrote out a manifesto on wild politics. With encouragement from Maria and Gena Corea to write a book, instead I began doing the research and in 1998 I enrolled to do a PhD which did become the book Wild Politics: Feminism, Globalisation and Biodiversity. Twenty years later what started as an update turned into a new book, Vortex: The Crisis of Patriarchy. In this I write about many subjects not included in Wild Politics such as disability, prostitution, violence against lesbians and transgenderism as well as many areas that were included such as the violence of colonisation, biocolonialism, bioprospecting, dispossession, neoliberal economics and ecological destruction.

In late 1994, as a way of stepping aside from big events, I joined first the Women’s Circus and secondly, the Performing Older Women’s Circus (you had to be over 40 to join this). I trained as an aerialist and loved every minute of it. There is nothing like being on a trapeze or a tissue to focus the mind. You simply can’t think about all your worries. I participated in lots of performances, wrote some scripts and eventually began to combine poetry and aerials in solo performances. It was like a return to my childhood days of climbing trees and hanging about in the woolshed. After that extreme physical training, I decided to begin studying Sanskrit in 2007. Sanskrit is an extreme mental exercise and still takes up at least two days of my week.

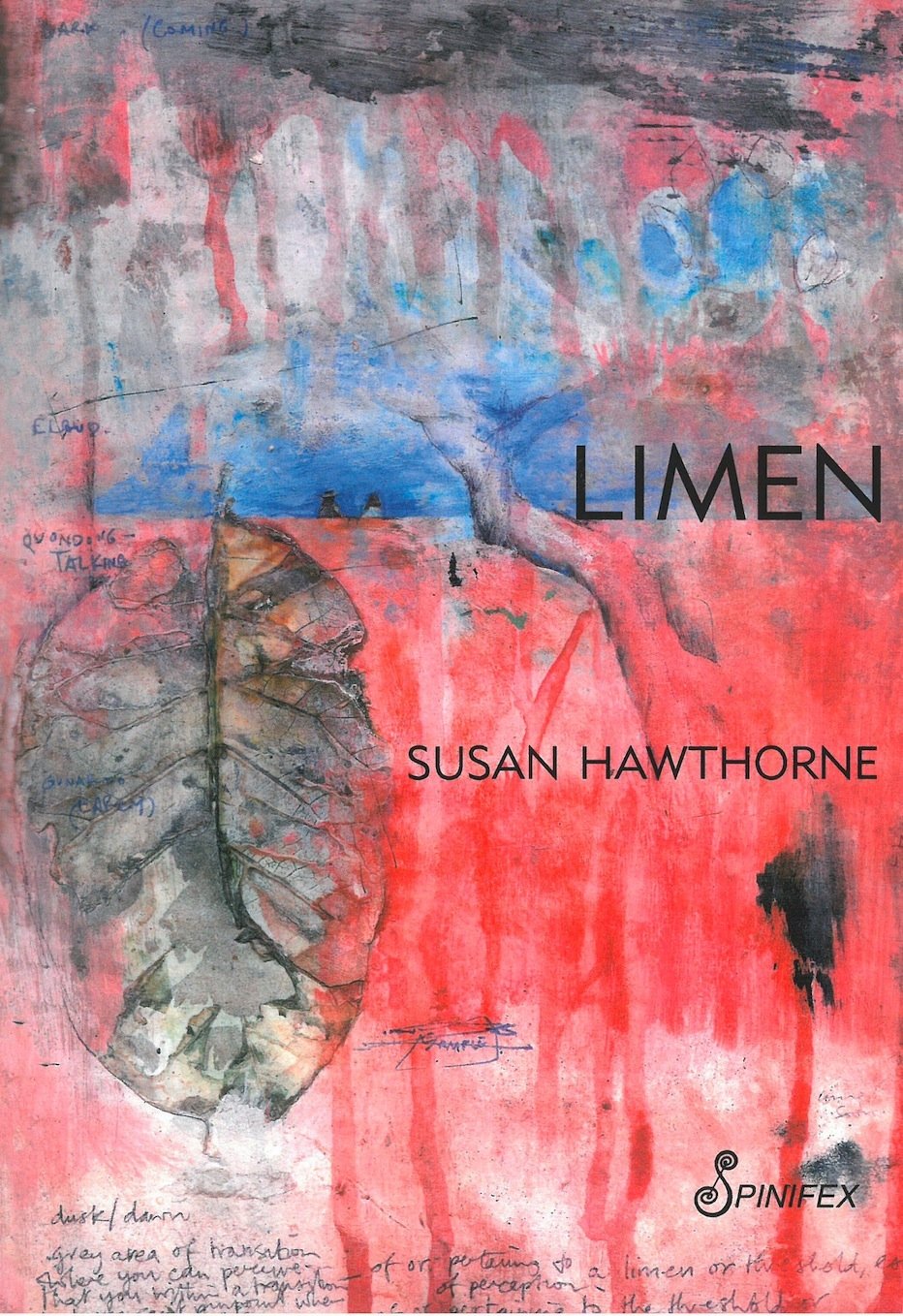

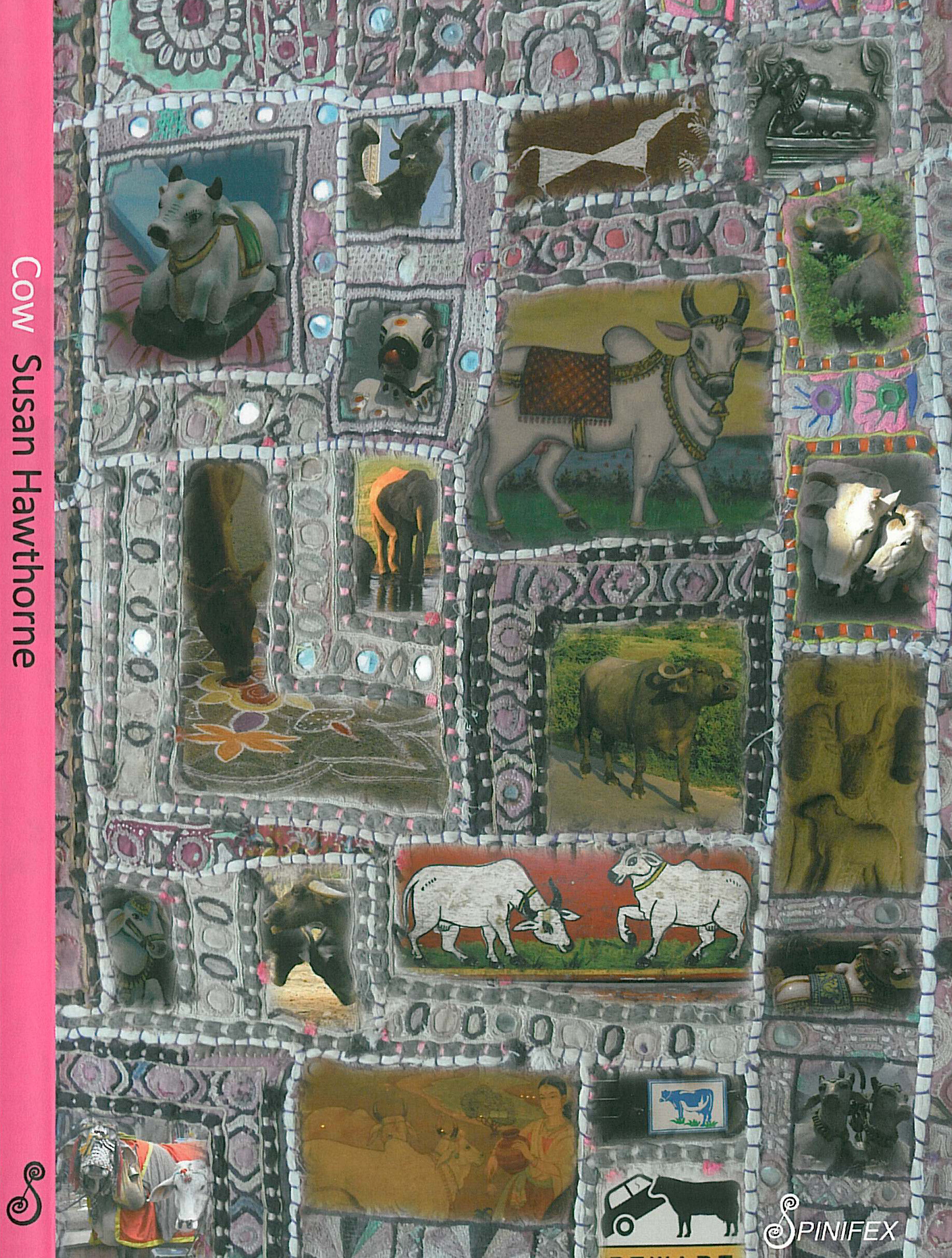

Throughout all this time I have been writing. The Falling Woman took ten years and my second novel, Dark Matters, fifteen. The latter is a novel about lesbians who are attacked in a vicious night raid, one of whom is arrested, the other is assumed dead. It took me years to do the research and to find a way to write about trauma without scaring off the readers. In between, I wrote a lot of poetry and had two literature residencies with four months in Chennai where I wrote Cow and six months in Rome where I wrote Lupa and Lamb. These residencies gave me time to escape the daily publishing routine.

Spinifex continues with around 270 titles available despite so many occasions on which our books are not reviewed, our authors not interviewed. Many have been translated and we have had to be inventive e.g. by beginning to produce ebooks in 2006 and, since COVID-19, zoom launches that have kept up our profile in Australia and internationally.

My radical feminist and lesbian journey has often been surprising. It is a mix of political and literary activism. My joys have been sharing a life with Renate Klein and our dogs, travelling in Australia to lots of out of the way places, having the chance to travel overseas, and meeting so many wonderful women who have enriched my life many times over. I love to work with women, to read women’s stories and to participate in feminist activism with women. Finally, I want to keep talking about lesbians because many terrible things have happened to lesbians not because of what we have done but because of who we are. But deciding to be a lesbian is still the best decision of my life.